(It had been a while since I managed to find the time to write something worth posting in the blog. Since I had to anyway write a speech for my inaugural lecture at the VU Amsterdam, let me post it here and hopefully motivate me to write more frequently. The slides and the recording of the lecture can be found in the talks page)

Dear Dean of the Faculty of Science, Professor Aletta Kraneveld, dear colleagues of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and of Nikhef, dear friends and family,

Many thanks to everyone for joining this inaugural lecture. Today I wanted to tell you about the incredible inner life of the humble yet amazing proton, the building block of all matter around us. But before delving into the proton, I wanted first to briefly reflect on the highly non-trivial fact that we can actually be here, discussing the fine details of something that is so far away from our everyday experience as the internal structure of subatomic particles.

Since the dawn of time, when mankind first developed self-conscience, we keep repeatedly asking ourselves questions such as who are we? What are we made of? What is the stuff around us made of, and can we transform it? Looking up and contemplating the heavens, we have admired their immensity and beauty, and asked ourselves what is our place in this cosmos. The asymmetry between our apparent fragility and the immensity of the universe has been recognised and addressed in various ways by cultures and religions across history.

This breathtaking picture was taken recently by the James Webb Space Telescope, and is popularly known as the Pillars of Creation. It illustrates the vertigo that contemplating and trying to make sense of our Universe may induce. Psalm 8 of the Old Testament summarises beautifully this tension, by writing

When I consider your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is mankind that you are mindful of them, human beings that you care for them?

Innumerable answers have been provided to this or variations of the same question. The Judeo-Christian tradition provides a possible answer, since the psalmist continues by writing

You have made them a little lower than the angels and crowned them with glory and honor

To me, the message here is that humanity has been given a most amazing and unexpected gift: the ability of rationally comprehending how our world works. Indeed, Nature is not described in terms of the capricious wishes of warring gods, or by some chaotic concatenation of unrelated phenomena, but rather by universal laws which we can formulate, discover, verify, and generalise. Modern science is built upon the realisation that, first, careful observation and measurements are instrumental to identify these universal laws, and, second, that mathematics is the language in which these laws should be expressed.

Let me move from the beautiful Space Telescope pictures to the somewhat more austere set up of particle physics, in this case the muon g − 2 experiment at Fermilab. While you are unlikely to hang this picture in the wall of your living room, in a sense it is embedded with a beauty as compelling as the one from the Pillars of Creation. Why? In this experiment, scientists measure with an extremely high precision proper- ties of elementary particles, something called the anomalous magnetic moment of the muon. In parallel, after many years of computing some formidable integrals, we can achieve a theory prediction of comparable precision. To give you an idea of what is being achieved here, the analog of the precision reached both in the experiment and in the theory calculation is that of measuring the Earth-Moon distance and trying to get the answer right at the millimeter level. In this case, data disagrees with the experiment by a tiny yet significant amount, which could point to yet-to-be discovered phenomena.

Being able to make sense of such abstruse properties of elementary particles, so far away from our everyday experience, induces an amazement which to me is no different from that that prompted the Psalmist to reflect upon our place in the universe. The same considerations drove the physicist Eugene Wigner to write his famous treatise where he stated that

The deep unreasonable efficiency of mathematics in science is a gift that we neither understand nor deserve.

This gift, this language that we can use to talk to Nature, is indeed one of the most beautiful ones mankind has ever received, as Bertrand Russell wrote

Mathematics possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty, cold and austere, like that of sculpture … The true spirit of delight, the exaltation, the sense of being more than Man, which is the touchstone of the highest excellence, is to be found in mathematics as surely as in poetry.

Modern science blossoms in this combination of experimental observation and mathematical modelling, and the study of elementary particles is no exception. The goal of this lecture is to guide you through the world of proton structure, so that you can join us in the amazement of the many remarkable surprises that we will encounter in the way.

Look around you. What do you see? An extremely complex world, full of different objects, colors, textures, materials. It seems, naively, a most peculiar hypothesis to state that the fish, the lake, the house, the human, and the camera itself used to take this picture are just made up of exactly the same building blocks.

Indeed, our modern understanding of Nature as composed by different configurations of the same building blocks, namely atoms, which in turn are obtained by combining protons, neutrons, and electrons, is so highly non-trivial that the famous physicist Richard Feynman once stated that:

If, in some cataclysm, all of scientific knowledge were to be destroyed, and only one sentence passed on to the next generation, what statement would contain the most information in the fewest words? I believe it is the atomic hypothesis that all things are made of atoms.

To begin, we can take a closer look at the water in the lake. If we look real close, we eventually see that at some point water is composed by identical molecules of the form shown here, with one oxygen atom attached to two hydrogen atoms. Hence, all properties of water, including their melting and boiling points which ultimately determine that Earth can accept living forms like ourselves, depend on the specific arrangement of these three atoms. And what is then an atom? We learn in high school that a hydrogen atom is some kind of miniature solar system, with a nucleus made of a proton and with an electron orbiting gracefully around it. Hence: when we look closely at water, we can identify individual water molecules, when we look closely at water molecules, we can tell apart hydrogen from oxygen atoms, and when we look closely at hydrogen atoms, we can separate protons from electrons.

Can this Matrioska doll construction go on forever? What happens if now we aim to look deeper into the proton? As you know, to be able to visualize small objects we need good microscopes. The question is: what kind of microscope should I use to image an object as tiny as a proton?

The first optical microscope was invented by a fellow Dutch scientist, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, actually within walking distance of the first apartment that we rented in Delft when we moved to The Netherlands. However, optical microscopes can resolve cells and bacteria, but to image matter with higher resolution we need to use electrons, rather than light, as a probe. For instance, using a Transmission Electron Microscope, one can image individual atoms, in this case of a graphene monolayer. But even these powerful microscopes are not able to resolve the inner structure of protons, for which I need a very different type of microscope. And what this can be?

In particle physics, we use something called “particle colliders” as the world’s most powerful microscopes. Particle colliders are based on the somehow unimaginative but always successful concept of brutally smash- ing things together to break them and see what was inside. The most powerful of such colliders ever built by humankind is the Large Hadron Collider, underneath the beautiful outskirts of Geneva and hosted by CERN, the European Laboratory for Particle Physics, where VU and Nikhef colleagues play leading roles in several of its experiments.

How does this “proton microscope” work? The principle is conceptually simple, but realising it is devilishly complicated. We take a large number of protons, compress them into a bunch no greater than a bacterium, accelerate them to almost the speed of light within a tunnel of 27 kilometers, and then we make them collide head on. And this is no easy feat: you need to keep a tiny bunch of subatomic particles, mov- ing at almost the speed of light, perfectly aligned while covering three times the length of the Amsterdam North-South metro line.

This animation displays a simulation of a collision from the ATLAS experiment. First of all, we must go 200 meters underground, where we find the LHC tunnel. In this tunnel, we encounter the proton beam pipe, where superconducting magnets are responsible for accelerating and steering the protons. As we see in this animation, protons are composite objects, and the behaviour of these constituents will determine the outcome of the collision. Protons are accelerated until eventually they move to almost the speed of light, and then we made them collide. By reconstructing the debris of these spectacular collisions, scientists can learn what are the rules dictating the behaviour of elementary particles at the smallest distances we have ever resolved, millions of times smaller than the size of an atom itself.

Accumulating data from the LHC and other experiments, we have developed a reasonably good picture of the proton. Going back to our Matrioska construction, if we “open” a proton, what do we find? The short answer is “it’s complicated”. In technical jargon, what a proton contains depends on the type of mea- surement and in particular on the resolution with which you are imaging it. First, we see that the proton contains three particles known as “quarks”, with the peculiar property that their electric charge is a fraction of than of an electron. Demonstrating once again that physicists are hopeless in branding, these quarks were denoted by the unimaginative names of “up” and “down” quarks. If we look more closely, we also find other types of quarks in the proton, generated by the sea of quantum fluctuations, as well as “gluons”, these little springs that keep the quarks bound together within the proton. And if we look even deeper, corresponding to particle collisions of yet higher energy, we can find that the proton contains photons, weak gauge bosons, or even Higgs bosons. The proton thus reveals itself as a fascinating micro-universe, with its own rich inner life.

Let us try to visualize this micro-universe that the proton is. This animation shows how the structure of the proton varies as a function of a variable called Bjorken-x, which is the fraction of the proton energy which is carried by a specific quark or gluon. First, we have relatively small values of x, which corresponds to proton constituents that carry a small amount of the total energy. In this configuration, the proton appears to be dominated by an immense sea of matter and antimatter quarks, as well as of gluons. As we move towards higher energy fractions, the density of constituents decreases, and we start identifying dominant components. For large values of Bjorken-x, three quarks (two up and one down) share the totality of the proton’s energy, so there is little “space” for other types of constituents.

By combining experimental data with precise theoretical calculations and cutting-edge statistical meth- ods, we can therefore scrutinise the proton with a two-fold motivation. On the one hand, we want to address fundamental open questions about Quantum Chromodynamics, the quantum theory of the strong nuclear force. These questions include: How does the mass and spin of protons arise in terms of its constituents? What is the antimatter content of protons? Under which conditions a proton behaves as purely gluonic matter? On the other hand, we also want to use the proton as an instrument, as a tool to achieve scientific goals such as searching for yet-unknown particles at the LHC, detecting neutrinos from the cosmos, and studying the quark-gluon plasma, the hot and dense medium that permeated the early Universe.

Proton structure is an area of research that has delivered many exciting results in the recent years. These include evidence that the gluon contributes to the proton spin, that all-order gluon resummation is required to describe electron- proton scattering at high energies, and that the proton contains constituents heavier than itself. Beyond its recognition by the academic community, I also find a positive development that newspapers and science media outlets acknowledge that the proton is something worth writing about – and that the public loves to learn about. And I think this interest is fully justified: after all, the proton is, together with the electron, the building block of all matter surrounding us.

I will come back to one of this recent discoveries, namely that of charms quark in the proton, in a few minutes. But before, I wanted to tell you about how we use Artificial Intelligence to learn about the behaviour of the proton constituents, and use this opportunity to reflect on the role of failure and delayed reward in the scientific enterprise.

My fascination for high-energy physics began 21 years ago, in a lecture about Elementary Particles at the University of Barcelona. My soon-to-be PhD advisor, Professor Jos ́e Ignacio Latorre, had just written down in the blackboard the Lagrangian of Quantum Electrodynamics, the theory that combines electromagnetism with Quantum Mechanics. I remember that he stared for a few seconds at these equations, and then he told us that:

The beauty of these equations may not be appreciated upon a first glance, but what happens with the equations of particle physics is no different from truly enjoying a masterpiece by Beethoven: you need a sufficient degree of maturity to be able to truly appreciate their deep elegance.

This quote is a personal recollection, so very likely I have embellished it over the years, yet it led me to realise that this kind of research was exactly what I wanted to do as a PhD: to admire the beauty and the order of the world of fundamental particles. And indeed, a few months afterwards, I started my PhD trajectory in the group of Jose Ignacio Latorre.

However, in contrast with my naive expectations, the project that I was proposed appeared to me particularly ugly: to use some obscure numerical technique called “neural networks” to “learn” the properties of the proton from the data. So while all my graduate school colleagues were enjoying PhD projects in fancy topics like black holes, string theory, super-symmetry, of extra dimensions, I was stuck writing thousands upon thousands of lines of Fortran 77 trying to get these neural networks to learn the data on a rather boring and down-to-earth particle as the proton. Spoiler alert: this initial assessment was completely misguided.

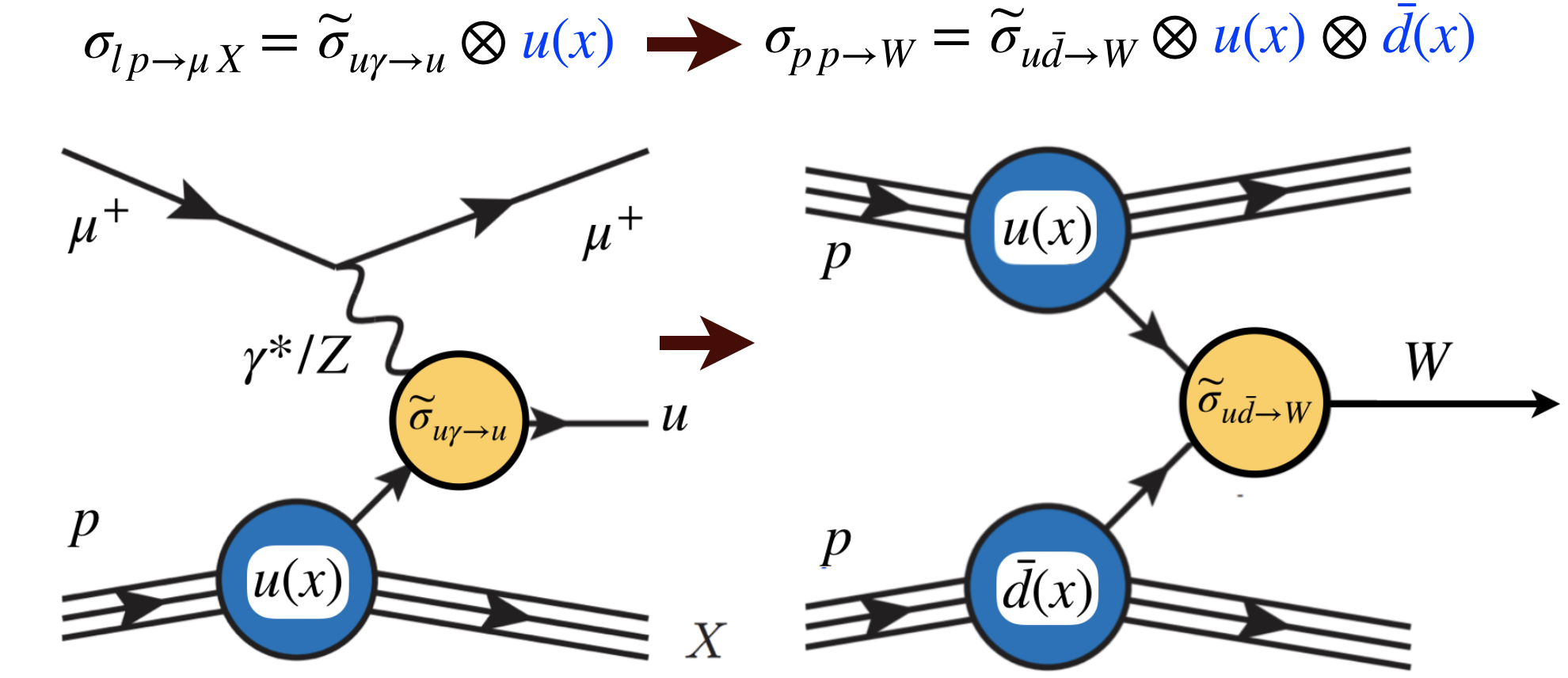

The idea of my PhD project, which has been at the core of my research program since then, was the following. Assume that you would like to predict the outcome of a specific process arising at the LHC, in order to compare our current best theories with the data. The outcome of such prediction depends on the properties exhibited by the quarks and gluons inside the proton. For example, assume that we want to produce a W boson, which is a sort of heavier sibling of the photon. Producing this particle requires finding, inside of the two colliding protons, an up quark and a down antiquark carrying specific fractions of the proton energy. Therefore, to predict the number of W particles that the LHC will produce I need to know the probabilities of finding up quarks and down antiquarks in the proton with the appropriate amount of energy. These probabilities are described mathematically by objects known as parton distribution functions, or PDFs for short. It is not possible, with current technology, to directly compute these PDFs and we have to extract them from the data.

The traditional approach was to assume some model for these PDFs, say a relatively simple functional form, and then to fit its parameters from the data. This approach was far from ideal, essentially due to the bias introduced: the results one obtained were heavily influenced by unjustified assumptions about the chosen PDF model. And this was not a merely academic consideration: by the time I started this research, two large experiments had already claimed evidence for new phenomena that were later revealed to be artefacts of a mismodeling of the proton structure.

To bypass these limitations, the solution we adopted was to use machine learning techniques, in particular feed-forward neural networks, to parametrise the proton PDFs. Why neural networks? Because of a remarkable property known as the universal approximation theorem, which states that sufficiently flexible neural networks can reproduce any behaviour encoded in the data, no matter how complex. With this strategy, PDFs are determined by combining neural networks with QCD calculations and broad dataset composed by thousands of independent measurements. Our Neural Network PDF approach, or NNPDF for short, enables the model-independent determination of the behaviour of the quarks and gluons in the proton, which is then used to inform theory predictions of interesting processes at the LHC and elsewhere.

Let me show you our most updated picture of the quarks and gluons inside the proton, while at the same time illustrating how neural networks are trained to reproduce the data. In this animation, you see many curves describing the up antiquark (in blue), the up quark (in orange) and the gluon (in green). Each of these curves corresponds to a possible solution of the PDFs, and their spread reflects the associated uncertainty. At the beginning of the training, the neural network has never seen the data, so there is a very large spread among the candidate solutions. As the training advances, the network learns that some solutions are disfavoured by the data and are hence discarded. We can see how the spread decreases, even if some outlier solutions, far from the bulk, remain. At the end of a satisfactory training, the curves for each PDF are reasonably similar. Our goal is to reduce this spread as much as possible, since this would lead to more precise predictions for LHC processes.

This NNPDF approach has been continuously improved across the years, both in terms of the underlying data and theoretical calculations, as well as in terms of the machine learning techniques implemented. It has also been applied to new fields beyond its original scope. Some recent achievements made possible with this strategy are highlighted here. We found evidence that the proton contains charm quarks, constituents heavier than itself, as I will explain in the last part of the lecture. We have shown that when protons are embedded into heavy nuclei, such as lead, a rich pattern of nuclear modifications such as shadowing arises. We have connected the LHC with cosmic neutrino detectors by using QCD and PDFs as a theoretical bridge. And we have quantified how the structure of the proton is modified in the presence of new fundamental interactions, beyond those of the Standard Model of particle physics .

Looking back, one of the achievements I am most proud of is that our NNPDF results were used for the theory predictions entering the ATLAS and CMS Higgs discovery papers in 2012. I was actually a research fellow at CERN at the time, and after queuing for hours I managed to be present in the conference room for the big announcement, close to Peter Higgs himself. It felt amazing to be part of history being written, and also knowing that we have provided our modest yet non-negligible contribution to this milestone discovery. It is also illustrative to visualize the cumulative impact of our results by assessing how frequently the LHC experiments use them. From this overview, one reads that more than half of the hundreds or even thousands of ATLAS and CMS analyses presented so far use NNPDF results. Actually, the NNPDF3.0 determination [12] is the highest cited paper written in particle physics based on applications of machine learning.

Why am I emphasizing here this impact? Because remember, we began with this project way before Artificial Intelligence became the world-changing technology that it is now. Back then, research in this topic was called at best “niche”, and at worst irrelevant and “not even physics”. That meant research which was ignored by peers, where it was challenging to get published, and which ended up with my conference talks in the typical session where the conveners bundle the topics they don’t know where else to put. In hindsight, Jos ́e Ignacio Latorre’s choice of my PhD topic was both far-sighted and very risky, and during many years I could not resist the nagging feeling that I had made a wrong choice.

We can now be rightly proud of these nice achievements, but a disclaimer is essential: this “success story” has only been possible following many years of rejection, frustration, and un-rewarded hard work. It all started with an unlikely, peculiar, and far-fetched idea at odds with the hype and low-hanging fruit that often dominates scientific research. It took us no less than 10 years to reach the level in which our results became competitive with those from other groups, and those years were definitely not a fun walk in the park.

We live in a culture that primes immediate satisfaction, and science funding is no exception with short-term, low-hanging returns often being prioritised. But in many cases, there are just no short cuts, and the path less traveled is indeed the one we should follow. I am therefore immensely grateful to my PhD advisor, Professor Jose Ignacio Latorre, for proposing me to take this road, even when it often felt like traveling across a barren wasteland. He was right all along, and even more, like he always told me, the best was yet to come.

The final topic I wanted to discuss in this lecture is our recent study of charm quarks in the proton. For this topic I will switch to Dutch: after all, I deem it only fair that part of my inaugural lecture as professor in a Dutch university takes place in the language of the country that has so amazingly welcomed me

Een van de grootse raadsels in de wereld van elementaire deeltjes is het feit dat er bestaan drie zogenaamde “generaties” van materiedeeltjes. Ik bedoel: we hadden al over up en down quarks (die zijn de eerste generatie), maar men heeft ontdekt ook “strange” en “charm” quarks (tweede generatie) en ook “bottom” en “top” quarks (derde generatie). De drie generaties van quarks delen identieke eigenschappen, bijvoorbeeld up, charm, en top quarks hebben hetzelfde elektrische lading. Het enige verschil is hun massa: up en down zijn lichter, bottom en top zijn zwaarder. Waarom drie generaties, en niet een of twintig? Waarom een topquark is veertigduizend keer zwaarder dan een up quark? We hebben geen flauwe idee, helaas.

Maar wat heeft dit te maken met het proton, ik hoor jullie denken? Nou, een proton weegt ongeveer een giga-elektronvolt. Een giga-elektronvolt is een handig meeteenheden in de wereld van elementaire deeltjes. Een charm quark, die “zwaardere neef” van het up quark, weegt ongeveer 40% meer dan een proton. Het zou best gek zijn als protonen bevatten charm quarks, toch?

Stel, jij ontvangt een pakketje, en die pakketje weegt een kilo. Valt mee, niet zo zwaar. Maar opeens, als je het pakketje opendoet, de inhoud weegt 2 kilo’s! Hoe kan dat? Zo’n vreemde situatie is uiteraard verboden in ons dagelijkse leven, maar het komt voor in de opmerkelijke wereld van de kwantummechanica.

Waarom? De beroemde gedankenexperiment van de kat van Schroedinger mag ons hier misschien helpen. Stel, je neem en kat, of zelf een poes, en die wordt opgesloten in een doosje. Binnen het doosje is er en mechanisme met gif dat heeft 50% kans om de arme kat te doden. Let op: die zijn verzonnen katten, geen poes heeft geleden tijdens dit gedankenexperiment. Nou, volgens het principe van de kwantumsuperpositie, voordat een waarnemer het doosje opendoet, het kat zit in een superpositie van leven en dood. Pas op: de kat is niet leven OF dood, maar daadwerkelijk leven EN dood tegelijkertijd.

Hetzelfde redenering zou voor charm quarks binnen het proton gelden. Het proton zou misschien een kwantum superpositie zijn van staten zonder charm quarks (lichter, met grote kans) en van staten met charm quarks (zwaarder, maar met een piepkleine kans, anders de massa van het proton zou niet kloppen). Dit aanname heet “intrinsic charm” en werd voorgesteld meer dat 40 jaar geleden. Kleine probleempje: tot nu toe, er was geen hard bewijs voor die staten van het proton met charm quarks, en er was dus werk aan de winkel voor ons.

Met die motivatie, vorige jaar voerden wij een analyse en probeerden wij de charm inhoud van het proton te bepalen. Heel kort samengevat: wij hebben alle beschikbare metingen vanuit de LHC en andere experimenten gecombineerd met de meest nauwkeurig theorie berekeningen, en in het bijzonder hebben we verwijderd effecten waar charm quarks komen niet uit het proton, maar worden geproduceerd via stralingsemissie.

Het resultaat van ons kunstmatige intelligentie analyse was dat, inderdaad, het lijkt dat charm quarks zitten in het proton. Verder, de statistische significantie van ons resultaten waren hoog genoeg om te bew- eren dat we hebben evidence (bewijs) van intrinsic charm gevonden. Heel toevallig, wanneer we waren ons analyse aan het afronden, kregen wij een onverwachte bevestiging. Volledig onafhankelijke metingen van het process “Z+charm” vanuit het LHCb experiment bij CERN, waar ook VU-collega’s zijn nauw betrokken, blootleggen dat zonder intrinsic charm (groene puntje) die metingen kloppen helemaal niet. Integendeel, wanneer rekening wordt gehouden met intrinsieke charm, er is een goede overeenkomst tussen data en theorie.

Dus ja, na een zoektocht, of beter gezegd een speurtocht, van 40 jaar, hebben we nu eindelijk bewijs dat charm quarks bestaan binnen het proton. In technische begrippen: zoals we zie in dit animatie, het proton is een kwantumsuperpositie: het zit meestal in een up-up-down configuratie, maar soms, heel kort, er ontsta een fluctuatie naar een up-up-down-charm-anticharm configuratie. Dit resultaat is zeker te gek, onze dagelijkse ervaring schreeuwt “dat kan niet”, maar het is gewoon toegestaan in de kwantum wereld. Sterker nog, en nog belangrijker, dit bevinding is in goede overeenstemming met de experimentelle data, en in de wetenschap die zijn altijd de hoogste rechter.

Ons resultaten kregen best wat aandacht binnen en buiten de deeltjesfysica gemeenschap, en zelfs Ned- erlandse outlets zoals De Volkskrant of New Scientist hebben over gehad. En ik vind dat zo’n interesse is terecht: niet iedere dag ontdekt men een nieuw onderdeel van een van de belangrijkste deeltjes in het Universum: het proton. En zoals gebruikelijk in de wetenschap, goede resultaten leiden tot nog meer vragen. Bijvoorbeld, nu zijn wij bezig met het studeren of er is een asymmetrie tussen intrinsic charm quarks en antiquarks binnen het proton, en of er bestaan nog steeds zwaardere quarks, zoals intrinsic bottom quarks. Dus als wij zeggen altijd, stay tuned.

I would like to conclude this lecture by briefly highlighting some possible directions for future research on proton structure. First of all, the Large Hadron Collider will continue its operations for two more decades while significantly increasing its luminosity, offering unique opportunities for particle physics. An accurate understanding of proton structure becomes more important than ever in this high-luminosity LHC era. For instance, high-precision measurements such as the W boson mass, for which there is a startling discrepancy between LHC and Tevatron measurements, are most sensitive to the modelling of proton structure. PDFs are also relevant for direct and indirect searches for new phenomena, and we should be careful that we do not misinterpret as New Physics effects that can be explained by proton structure, as could happen for the forward-backward asymmetry in high-mass Drell-Yan production.

Furthermore, LHC proton collisions also produce an immense amount of ghostly particles known as neutrinos. Neutrinos are extremely difficult to detect because of their very feeble interactions, and until recently they simply escaped the LHC detectors and were hence lost for science. With the discovery, two months ago, of LHC neutrinos, whole new directions for particle physics open up. High in my to-do list is to exploit this neutrino beam to probe the proton in unexplored regions, and in particular to identify new states of matter entirely dominated by gluons.

Another exciting opportunity will be provided the Electron-Ion Collider, to be built in the US and start operations in the coming decade. The clean environment of lepton-proton and lepton-nucleus collisions will offer an unprecedented perspective on hadron structure and on heavy nuclear dynamics. In particular, the EIC enables the first universal determination of quantum correlation functions, integrating unpolarised and polarised proton PDFs with nuclear PDFs and fragmentation functions.

With this perspective ahead of us, it is clear that we have enough to keep us very busy in the coming years in our quest to achieve a deeper understanding of the proton, and in doing so tackling some of the most pressing open questions in particle physics.

I could not end this lecture without expressing my infinite gratitude to all my collaborators with whom I have worked together along the years in the various projects that I discussed in this lecture. Special thanks are due to my PhD co-supervisor, Professor Stefano Forte, whose brave leadership of the NNPDF Collaboration has been instrumental in its success, and who has been always for me the highest example of passion, excellence, and integrity. All the results presented here are truly the outcome of team effort, and I have been blessed to work always with such outstanding and motivated researchers, specially the many incredible PhDs and postdocs whose energy has driven many of the projects. Despite the popular misconception of a scientist as a lone genius, science is today, more than ever, a team effort, with excellence thriving in collaboration, rather than in competition.

My final words are for Professor Piet Mulders, the previous holder of the Chair in Theoretical Physics which I now occupy. Professor Mulders is one of the founding fathers of the modern science of hadron structure, and his research has been extremely influential to shape our field. It is for me a great honor to follow the steps of a giant such as Piet, who trusted and supported me from day one, and I am really grateful that he is present today with us.

With this, I would like to conclude my inaugural lecture. Professor Kraneveld, colleagues, friends, and family: many thanks for your attention, and please stay tuned for exciting news about the proton.